In this guest post by Andras Gerlits, creator of omniledger.io, we’ll look at what the UK and EU operational resilience legislations mandate and how they try to steer financial institutions towards less exposure to 3rd-party ICT-provider risk. We’ll talk about how we can turn legal problems into technical ones using advances in computer science and software engineering, and how these challenges can be turned into opportunities.

Except when specifically discussing the text of the EU legislation, we’ll use ‘DORA’ to refer to requirements present in both (current and upcoming) UK guidelines and EU regulations.

Introduction

Much like SOX, which led to widespread anti-corruption measures in its wake all over the world, DORA disrupts the status quo by placing the responsibility for looking after certain kinds of risks on management. The legislation calls systemic dependence on 3rd-party ICT vendors a “concentration risk” and it stops just shy of imposing strict limits on reliance on these services. What it does instead is shift the responsibility for operational resilience onto internal processes, so that disruption from external services is kept within appropriate boundaries, and knock-on effects are mitigated as much as they can be.

In other words: DORA expects financial institutions to either not enter into contracts which expose their ‘critical or important’ functions to such external risks, or implement strict technical, governance and legal safeguards around potential disruption-events. DORA therefore makes it harder for financial institutions to rely on single-vendor solutions, both in terms of technology and governance. It’s clear that the challenges of building vendor-agnostic software, and the lack of ability to build resilient safeguards against potential disruptions, are not yet thought of as the central problem they should be.

The UK was actually ‘first to the party’ and published its rules and guidance on operational resilience back in March 2022:

As soon as possible after 31 March 2022, and by no later than 31 March 2025, firms must have performed mapping and testing so that they are able to remain within impact tolerances for each important business service. Firms must also have made the necessary investments to enable them to operate consistently within their impact tolerances.

But similarities don’t end there. The Bank of England is now running another public consultation with the specific aim to make their framework “interoperable” with EU and U.S. standards.

That’s not a bad thing. Vendor lock-in and ‘all eggs in one basket’ strategies are rarely in anyone’s best interests. An example is the horror story currently being played out following Broadcom’s acquisition of VMWare, which resulted in a multiple-fold increase in renewal costs for some users.

In a sense, all this aims at remedying the result of a kind of short-term thinking which exposes our financial system to a new form of systemic risk. To put it bluntly: the fact that a handful of ICT providers can hold an entire continent to ransom is a political problem. The EU Commission puts data sovereignty front-and-centre of its data strategy and the only way to guarantee sovereignty is to treat 3rd-party providers as commodities instead of relying on them as exclusive solutions, as most do now.

DORA in practice

Since DORA expects financial institutions to be able to explain fully what knock-on effects can be expected to any of its business functions due to the failure of any 3rd-party ICT provider, establishing the connection between vendors and business functions must be a central pillar of any DORA compliance strategy. In fact, DORA goes further than this and mandates that business continuity plans must also be established by the financial entity.

Vendors in this space often concentrate on Article 12’s focus on the recovery processes prescribed to the service providers, but often disregard the fact that business continuity presumes that all data needed for the affected business functions can be recovered from the (disrupted) main service-provider.

Financial entities shall put in place, maintain and periodically test appropriate ICT business continuity plans, notably with regard to critical or important functions outsourced or contracted through arrangements with ICT third-party service providers.

A new class of service called “Disaster Recovery as a Service” has popped up recently, which promises a painless solution to these problems. Some of these like Azure Recovery Service are clearly disallowed by the legislation, as DORA concentrates on the holistic risk posed by the vendor. Other such services are allowed as long as they can provide a way to recover all the functions and data within a predetermined time. This is only possible if the software envelopes all the operations of the cloud provider and acts as a “middle-man” between calls made to the main provider. This means that instead of one resilience problem we now have two, as any continued operation presumes that both the DRaaS service and the original provider work as expected. To put it differently: DRaaS can either fulfil business-continuity requirements or work without potentially disrupting our BAU operations, but they can’t achieve both.

It’s safe to say that it can be near impossible to establish this level of business continuity without first-hand experience in distributing operations between multiple providers safely. For management this means having actual distributed systems expertise at-hand, a specialism that Big Name consultancies can rarely provide.

How long is a piece of tangled up string?

Banks typically publish data feeds from their front office desks to downstream solutions like CRM or the Risk department. We call the intent to make data available for consumption by others a “promise”, as it clarifies the inherent risks involved. Consuming systems rely on these promises both directly and indirectly, by using data published by others. Some of these applications inform each other, back-and-forth (like Compliance and Risk), so looking in from the outside it can be unclear where essential information “originally comes from”. These promises (results) may feed a few hundred different systems, be maintained by many different teams across different countries and jurisdictions, and provide important or critical functions, the continuous operation of which make the difference between BAU and a weekend-long all-hands video conference.

Mapping out which promises inform which business function in this Gordian Knot is a daunting task by itself, but tracing back where (and through which 3rd parties) departments like “Cross-products” get all their information from, is a different level of complexity altogether.

DORA not only mandates establishing which business function is exposed to which external provider, but it also prescribes monitoring the liveness of the promised relationships. In such a heterogeneous environment, this requires careful analysis. Many already rely on 3rd parties for their monitoring, auditing, or logging, which makes designing mitigation strategies even harder.

Promise Theory

Managing systems by thinking in terms of promises is the defining idea behind the now ubiquitous Promise Theory, which has been behind a lot of the technology that scaled data centres for our modern cloud era. In their recent book Promising Digital Risk Management: What not to do in Cybersecurity, DevOps pioneers Burgess and DeBois argue (much like DORA does) for broadening our understanding of risk into two parts: disaster avoidance and disaster recovery.

Over the years, the Netflix technical blog has become a go-to source for discussions about large-scale system resilience. This article might already be more than a decade old, but what it says about the technical challenges and the strategies to minimise 3rd-party resilience risks are as up to date as the day they were written.

What can you promise?

DORA (and the recently published Technical Standards [PDF]) applies to services classified as both critical and important: in other words, anything that might negatively affect downstream clients, even slower-moving areas like reporting. It stipulates that providers must assess and ultimately promise downstream clients either a multi-vendor strategy for the dependencies they rely on for their own service reliability or at least the ability to recover quickly from 3rd-party disruptions. Most significantly, it requires an explanation on the rationale behind the chosen path.

Art. 6 §9: Financial entities may, in the context of the digital operational resilience strategy (…) define a holistic ICT multi-vendor strategy, at group or entity level, showing key dependencies on ICT third-party service providers and explaining the rationale behind the procurement mix of ICT third-party service providers.

These typical exposures are “Single Points of Failure” (SPoF). Having these means the risk to the entire enterprise multiplies with the introduction of each one. Even if the chance of a specific ICT provider’s failure is low, these events could have a devastating effect as they ripple throughout the wider system unless self-repairing failsafes are put in place.

Some causal factors in failure are technical, some stem from human negligence, and some even from intent to cause harm (e.g. rogue traders). Dan Luu’s public compilation of outage postmortem causes can be a real eye-opener.

The Future is Shared Consistency

Cloud providers differentiate their offerings by promising painless scaling on top of what is a commodity: computers connected over a network. Crossing the DORA-chasm is therefore an exercise in also commoditising those extra services that cloud providers give us beyond compute. Sharing load between different vendors (and potentially any data centre) is called a “hybrid cloud”.

A key part of any DORA-compliant data strategy is replication. If we are to free ourselves of critical dependence on a single cloud provider, and achieve the kind of resilience DORA mandates, we need redundancy. This means that safe and consistent replication across multiple locations and systems is essential.

Is safe and consistent replication actually promised by our data systems? We mostly assume that it is, but the truth is often far from this ideal. In the past, this has been a troublesome problem –easily solved for one system at a time, but impossible across related ones. Today, we have better answers to this, but the problem is subtle and often not well understood by engineers.

We can now build on 30 years of research to provide complete solutions to the data consistency problem. CFEngine applied self-healing contextual consistency to operating system and application level resources. We’ve seen how Kubernetes did the same for cloud workloads in recent years. These tools were both by-products of two important innovations: Consensus Groups and Promise Theory. Consensus Groups cover how different computers can agree on what (e.g.) the “current balance of bank account is” (think of the UK Post Office scandal), Promise Theory explains how these outcomes depend on promises and services working together.

The overlap between these two innovations is also where we can handle the larger problem of shared data consistency. Now we actually get inside the data streams and keep these promises for all shared data in a framework that is both more robust and easier to use. To address our compliance needs, we need an easy way for both developers and operations teams to work with these innovations. To turn this into an opportunity, we need better, safer tools that are just as easy to work with as those that cloud providers offer.

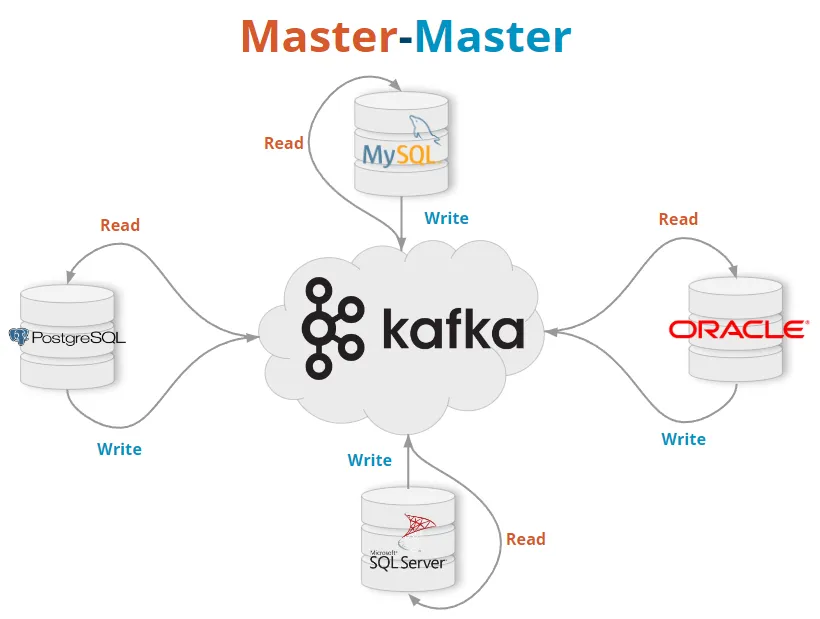

When I designed omniledger.io, compliance was at the forefront of my mind. Not only because I spent so much of my career integrating banking systems, but also because meeting requirements like disaster recovery, zero data loss or clear security is a good idea everywhere. I also wanted to avoid exposing developers and operations to extra complexity. Before I could do this, I needed to invent a new approach in the distributed data space. I patented and (together with Mark Burgess) published this new solution. These publications explain “the how”, but suffice to say that our data platform is a first in the industry able to solve the presented problems in a DORA-compliant way without expecting customers to radically change their existing infrastructure or even complicate their operational processes further. It achieves this by working transparently through established tools, namely: various SQL databases and Kafka.

There’s no reason DORA has to cause more bureaucratic, technical or governance complexity. In fact, it could turn out to be a way to simplify BAU operations substantially. Generating compliance reports for example, becomes trivial with a unified data-platform.

Summary

Having worked as an IT contractor in investment banking for over a decade (at 5 different institutions), I’ve experienced first-hand that they live on data. Thinking back, I can count on one hand the number of serious production incidents which were due to in-house software, but would quickly lose count of the ones which were due to disruption of some other system’s data feed.

DORA drags these concerns out of the tall grass to make providers promise due diligence to downstream clients. It’s a public safety issue. Though daunting for providers, this has the potential to become a change for the better. Now is the age of the platform solution. If we embed technical diligence into the platforms, we can indeed make those promises with confidence, and without having to hide behind legal liability protections. It’s time to modernise data systems for compliance. This will not only help with DORA compliance, but also simplify software development radically, decrease operational and infrastructure costs and simplify IT governance in one fell swoop.

Get in touch

Getting data strategy right is often the hardest part of the resilience puzzle. The Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA), and other similar measures, set a high bar for data resilience but also provide a good opportunity for us to consider data replication and redundancy properly, and ensure our solutions are safe and consistent.

If you’re interested to learn more about bringing consistency and resilience to your data infrastructure, get in touch via info@juxt.pro or book a time to chat.

Appendix

The following two sections are the most important, Articles 11 and 12, from the text of the DORA legislation that deal with business continuity requirements. Also cited is the most relevant section from Article 28, where the regulation defines the kind of failures that a financial entity needs to be prepared for, and finally a definition that clarifies the scope of this document.

Article 11, Response and recovery

1. As part of the ICT risk management framework referred to in Article 6(1) and based on the identification requirements set out in Article 8, financial entities shall put in place a comprehensive ICT business continuity policy, which may be adopted as a dedicated specific policy, forming an integral part of the overall business continuity policy of the financial entity.

2. Financial entities shall implement the ICT business continuity policy through dedicated, appropriate and documented arrangements, plans, procedures and mechanisms aiming to:

(a) ensure the continuity of the financial entity’s critical or important functions;

(b) quickly, appropriately and effectively respond to, and resolve, all ICT-related incidents in a way that limits damage and prioritises the resumption of activities and recovery actions;

(c) activate, without delay, dedicated plans that enable containment measures, processes and technologies suited to each type of ICT-related incident and prevent further damage, as well as tailored response and recovery procedures established in accordance with Article 12;

(d) estimate preliminary impacts, damages and losses;

(e) set out communication and crisis management actions that ensure that updated information is transmitted to all relevant internal staff and external stakeholders in accordance with Article 14, and report to the competent authorities in accordance with Article 19.

3. As part of the ICT risk management framework referred to in Article 6(1), financial entities shall implement associated ICT response and recovery plans which, in the case of financial entities other than microenterprises, shall be subject to independent internal audit reviews.

4. Financial entities shall put in place, maintain and periodically test appropriate ICT business continuity plans, notably with regard to critical or important functions outsourced or contracted through arrangements with ICT third-party service providers.

5. As part of the overall business continuity policy, financial entities shall conduct a business impact analysis (BIA) of their exposures to severe business disruptions. Under the BIA, financial entities shall assess the potential impact of severe business disruptions by means of quantitative and qualitative criteria, using internal and external data and scenario analysis, as appropriate. The BIA shall consider the criticality of identified and mapped business functions, support processes, third-party dependencies and information assets, and their interdependencies. Financial entities shall ensure that ICT assets and ICT services are designed and used in full alignment with the BIA, in particular with regard to adequately ensuring the redundancy of all critical components.

6. As part of their comprehensive ICT risk management, financial entities shall:

(a) test the ICT business continuity plans and the ICT response and recovery plans in relation to ICT systems supporting all functions at least yearly, as well as in the event of any substantive changes to ICT systems supporting critical or important functions;

(b) test the crisis communication plans established in accordance with Article 14.

For the purposes of the first subparagraph, point (a), financial entities, other than microenterprises, shall include in the testing plans scenarios of cyber-attacks and switchovers between the primary ICT infrastructure and the redundant capacity, backups and redundant facilities necessary to meet the obligations set out in Article 12.

Financial entities shall regularly review their ICT business continuity policy and ICT response and recovery plans, taking into account the results of tests carried out in accordance with the first subparagraph and recommendations stemming from audit checks or supervisory reviews.

7. Financial entities other than microenterprises shall have a crisis management function, which, in case of activation of their ICT Business Continuity Policy or ICT Disaster Recovery Plan, shall set out clear procedures to manage internal and external crisis communications in accordance with Article 13.

8. Financial entities shall keep readily accessible records of activities before and during disruption events when their ICT business continuity plans and ICT response and recovery plans are activated.

9. Central securities depositories shall provide the competent authorities with copies of the results of the ICT business continuity tests, or of similar exercises.

10. Financial entities, other than microenterprises, shall report to the competent authorities, upon their request, an estimation of aggregated annual costs and losses caused by major ICT-related incidents.

11. In accordance with Article 16 of Regulations (EU) No 1093/2010, (EU) No 1094/2010 and (EU) No 1095/2010, the ESAs, through the Joint Committee, shall by 17 July 2024 develop common guidelines on the estimation of aggregated annual costs and losses referred to in paragraph 10.

Article 12, Backup policies and procedures, restoration and recovery procedures and methods

1. For the purpose of ensuring the restoration of ICT systems and data with minimum downtime, limited disruption and loss, as part of their ICT risk management framework, financial entities shall develop and document:

(a) backup policies and procedures specifying the scope of the data that is subject to the backup and the minimum frequency of the backup, based on the criticality of information or the confidentiality level of the data;

(b) restoration and recovery procedures and methods.

2. Financial entities shall set up backup systems that can be activated in accordance with the backup policies and procedures, as well as restoration and recovery procedures and methods. The activation of backup systems shall not jeopardise the security of the network and information systems or the availability, authenticity, integrity or confidentiality of data. Testing of the backup procedures and restoration and recovery procedures and methods shall be undertaken periodically.

3. When restoring backup data using own systems, financial entities shall use ICT systems that are physically and logically segregated from the source ICT system. The ICT systems shall be securely protected from any unauthorised access or ICT corruption and allow for the timely restoration of services making use of data and system backups as necessary.

For central counterparties, the recovery plans shall enable the recovery of all transactions at the time of disruption to allow the central counterparty to continue to operate with certainty and to complete settlement on the scheduled date.

…

6. In determining the recovery time and recovery point objectives for each function, financial entities shall take into account whether it is a critical or important function and the potential overall impact on market efficiency. Such time objectives shall ensure that, in extreme scenarios, the agreed service levels are met.

7. When recovering from an ICT-related incident, financial entities shall perform necessary checks, including any multiple checks and reconciliations, in order to ensure that the highest level of data integrity is maintained. These checks shall also be performed when reconstructing data from external stakeholders, in order to ensure that all data is consistent between systems.

Article 28, General principles

8. For ICT services supporting critical or important functions, financial entities shall put in place exit strategies. The exit strategies shall take into account risks that may emerge at the level of ICT third-party service providers, in particular a possible failure on their part, a deterioration of the quality of the ICT services provided, any business disruption due to inappropriate or failed provision of ICT services or any material risk arising in relation to the appropriate and continuous deployment of the respective ICT service, or the termination of contractual arrangements with ICT third-party service providers under any of the circumstances listed in paragraph 7.

Financial entities shall ensure that they are able to exit contractual arrangements without:

(a) disruption to their business activities,

(b) limiting compliance with regulatory requirements,

(c) detriment to the continuity and quality of their provision of services to clients.

Exit plans shall be comprehensive, documented and, in accordance with the criteria set out in Article 4(2), shall be sufficiently tested and reviewed periodically.

Financial entities shall identify alternative solutions and develop transition plans enabling them to remove the contracted ICT services and the relevant data from the ICT third-party service provider and to securely and integrally transfer them to alternative providers or reincorporate them in-house.

Financial entities shall have appropriate contingency measures in place to maintain business continuity in the event of the circumstances referred to in the first subparagraph.

Article 3, Definitions

(17) ‘critical or important function’ means a function whose discontinued, defective or failed performance would materially impair the continuing compliance of a financial entity with the conditions and obligations of its authorisation, or with its other obligations under applicable financial services legislation, or its financial performance or the soundness or continuity of its services and activities;