Software is an ever-increasing part of our lives, and yet it is difficult and expensive to build systems that work accurately, reliably, and securely.

As part of our drive to building better data systems for our customers, we’ve identified a number of architectural principles we believe can yield better software systems.

These principles are brought together in a concept we’re calling ‘Atomic Architecture’.

As theorists, we’ve begun to discuss Atomic Architecture with like-minded software architects, many of whom have been influenced, as we have, by the significant benefits of functional programming languages.

As practitioners, we’re building a software stack that can greatly help with the implementation of systems that adopt the principles of Atomic Architecture.

But what are these principles? That’s what this blog article is about.

1. Shared State

In recent years we have seen a strong trend of autonomous development teams building micro-service based architectures.

While we recognise the reasoning and benefits behind this approach, there are some significant downsides. Firstly, there are obvious issues around the need for careful orchestration between services to meet business goals. But in addition, when business state is scattered across a number of services, it is more difficult to locate information and make ad-hoc queries across multiple services as you can with a single database.

Last but not least, if every service is responsible for storing its own state, every service must be kept secure to ensure its data cannot be accessed and written to from unauthorized parties. If state is kept in a single service, more resources can be dedicated on securing that service. This is the same reasoning for why you might store valuables in a bank vault.

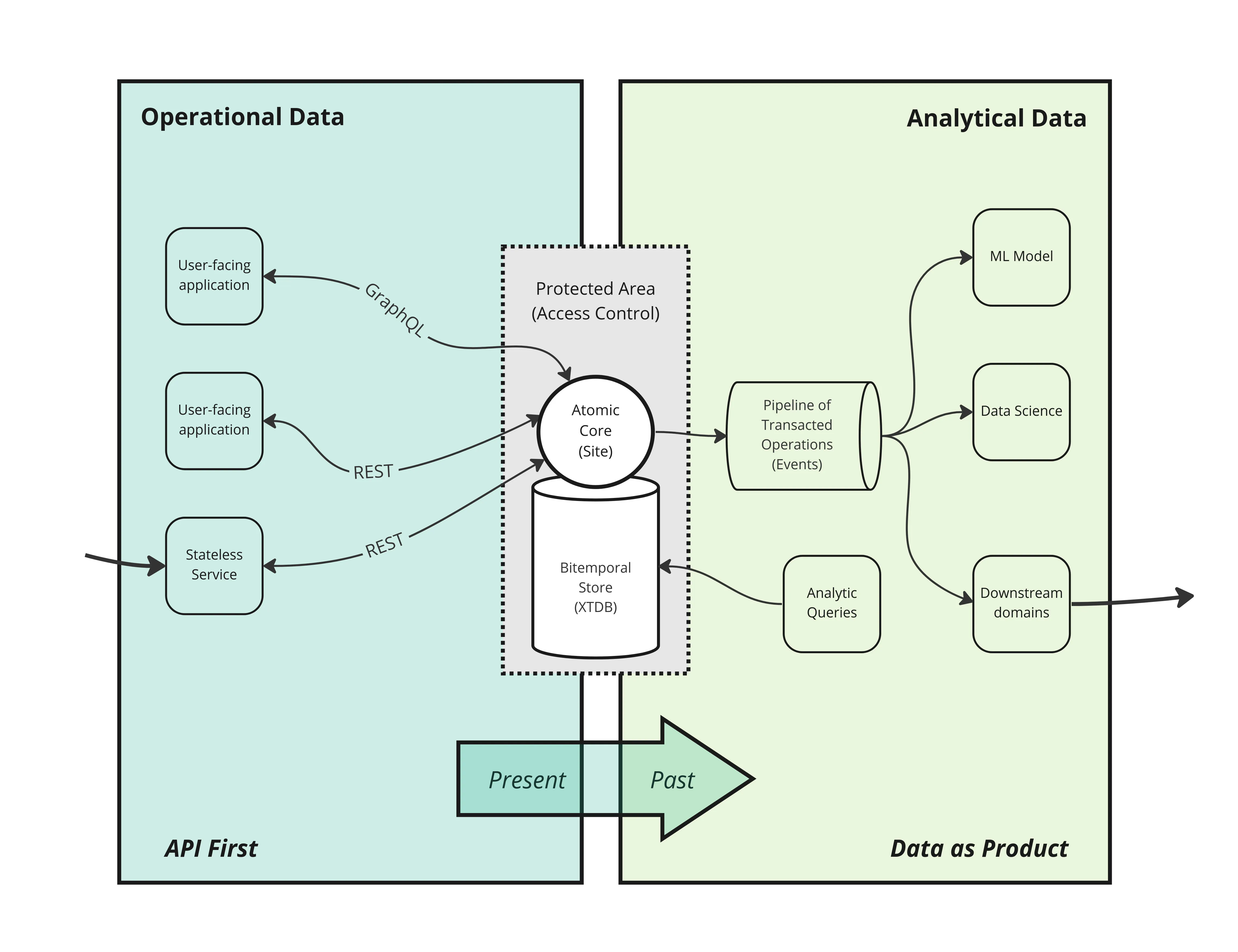

Rather than return to monolith-based architectures, we argue that much of the benefit of microservices can be enjoyed by separating functionality from state. We encourage the development of a diverse set of custom stateless micro-services, which focus on user journeys and goals. But we propose a policy that all such services, within a given domain, source and store their state in a single centralised service.

2. Domain Operations

Having separated out the state, we can now focus on the functionality of the system.

We break up the functionality into discreet atomic business-domain operations.

Each operation is given an name, unique within the domain. The name should indicate what the operation does.

For example:

- new-customer

- create-customer-account

- order-product

- invoice-customer

- refund-customer

For each operation, answers are sought to a series of questions, capturing the what?, how? and who can? of the operation.

Let’s take refund-customer as an example:

- What does it mean to refund a customer?

- What changes to the overall state of the system happen when a customer is refunded? For example, should a customer’s account balance be credited?

- What other effects happen when a customer is refunded, for example, should an email be sent to the customer?

- Who is authorized to initiate a customer refund?

Once answers to these questions are determined, we can implement these operations in code.

3. Contractual Interfaces

Having defined the business operations of the domain, now we focus on how these operations are invoked.

Our users will be interacting with applications, so we need to allow these applications to invoke these operations on their behalf. We can do this by building Application Programming Interfaces (APIs).

We see architectures where services are essentially state-less, sharing a central database for state. Services may well be managed by a container-based orchestration platform such as Kubernetes, and stateless services are easier to scale horizontally to respond to changes in demand.

However, if a database is accessible directly by services, the result is that services become tightly coupled to the database schema. As the number of services increase, the difficulty of rolling out changes to the database schema increases.

Inserting an interface or interfaces between services and the database can provide the necessary decoupling, allowing a greater freedom of independent evolution. Interfaces can provide to consumers a reliable and stable surface under which the database model may be evolving. So the database model can focus on the overall domain while interfaces can focus on providing the most appropriate data services to client applications. In some cases, a single interface might suffice. In other cases, there may be a need to provide a different interface to different classes of application.

By far the most dominant type of interface implementation is HTTP-based ‘REST’ interface consisting of individual endpoints which client applications can call with HTTP methods such as GET and POST. Other interface implementations might include GraphQL or gRPC, where appropriate. The type of implementation doesn’t matter so much.

What does matter is that all operations that may modify the data held in a database are made indirectly via requests to these interfaces rather than directly against the database.

4. Data Consistency

Consistent systems don’t allow two people to book the same hospital appointment, or sell you a product that is actually out-of-stock, or exhibit other similar anomalous behavior.

In short, consistent systems are systems that users can trust. They handle data with care, accuracy and precision.

When systems aren’t consistent, the inevitable mistakes and anomolies that occur must be handled manually, or worse, by layers and layers of additional code and workarounds, hugely adding to the system’s complexity, contributing to yet more anomolies.

Systems that aren’t consistent are also systems that are intractable. So mistakes end up being are brushed aside and complaining users are fobbed off.

Consistency should be a minimum standard that users can expect of their data systems. Yet all too often, consistency is negotiated away with dubious arguments about system performance or developer productivity.

The state of a domain is constantly changing. Yet, anytime that state is copied, it is potentially already stale. Any time a decision is made based on stale data, there’s a risk of making the wrong decision.

Yet, so many IT processes rely on copying data from one place to another.

In Atomic Architecture, we recognise that data needs to be made available to multiple systems. However, we carefully segregate the changeable data of the present (that a domain’s operations act upon) with the immutable data of the past (that can be safely shared with downstream consumers). This is the key to preserving consistency and re-esablishing trustworthiness as a guarenteed property of the systems we deliver to our users.

Technically, we want our operations to be applied to the domain’s state in a linear ordered sequence. For a given domain, there is only one official order of operations, and one ‘truth’ about how the state of the domain’s universe has occured. This is in stark contrast to architectures where multiple services all have their own ‘version’ of the facts.

For many implementations, processing a queue of operations using a single thread, provides sufficient performance. For implementations at the extreme end of the spectrum, more sophisticated algorithms are required to process operations in parallel and yet still preserve the property of linearizability.

5. Access Control

When we elect to share a single set of mutable state between all the applications of a domain, we run a greater risk that data might be accessed by unauthorized parties.

Therefore, we must ensure that every access to every item of data is subject to access control. This implies that we cannot rely on ad-hoc code to protect data, nor should we rely on retrofitting access control logic later in the development process.

For this reason, we state that, by default, every request by an application to an API should be accompanied by an access-token to identify the user the request is made on behalf of.

Of course, there are exceptions and some APIs offer public access to data. But, for the majority of the kinds of systems that we build within organisations, knowing who is making the request is an essential first step in determining whether and how to respond to the request.

In addition, it should be possible to easily inspect and manage which users have access to which resources. We don’t prescribe how this is done, but recommend that access control policies are determined for each and every domain operation.

6. Record Events

Our system has established the order of operations that have been successfully applied to the domain’s state. It is important to publish this ‘operation log’ downstream to consumers. Since each entry in the log indicates that a particualr operation has been applied at a certain time, we call this a log of events, or simply, an event log.

Consumers of these events may be looking for notification that a particular operation has occured. For example, an emailer may be triggered to send an email based on a send-email operation. This emailer may report the success or failure of the email via the remote API, yielding a further change to the domain’s state and yielding another event, for instance, ‘successfully-sent-email’.

Another consumer might be keeping a view up to date, for real-time analytics. Yet another might be training a machine-learning model.

7. Historic Versions

This is the last and perhaps most ambitious principle. In order to support our users well, we need to be able to understand our data systems. Subject to the necessary privileges, authorized parties should be able to gather as much accurate data about the system as possible, where necessary.

Ideally, this should include the ability to ask questions about the history of interactions with a system, not just the current state. We often need to understand how the current state occured.

Fortunately, there are an increasing number of enabling technologies to make this possible. The first is logs with infinite retention, like Kafka. There are also databases, such as Datomic, XTDB (and others) that support time-travel, allowing you to analyse state in the past.

Combined with a single order of events, a domain can create and make full use of an accurate record of its history.

If an operation contains logic/code, consider storing the program alongside the operation in the database.

Over to you

Write to me at mal@juxt.pro!

Notes

“Keeping your app-state in one place” — https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=34951014